About Me

I am an ex-Software Engineer who worked at Amazon Robotics from 2021 – 2024. I was the owner for the tier-1 path planning service responsible for 750K+ structured field robots, robots operating over localization tags arranged in a grid like manner inside a giant cage. I have extensive experience with designing and optimizing algorithms to solve business use cases – A* wrapped with an enormous amount of business complexity and spatial collision checks – and with designing robust, maintainable, and scalable cloud services with AWS (API Gateway, Lambda, Fargate, DynamoDb, S3). Working at such an immense scale, I also have a lot of interesting stories:

1. I brought down a airport connected warehouse that delayed planes from departing with packages and so naturally I had to stay up till 4 AM in the office to fix the mess I made.

2. I solved a 10+ year old bug that only showed up in ARM architecture

Before Amazon, I finished my bachelors from Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) in Robotics Engineering and Computer Science. I had an opportunity to explore wide areas of robotics including but not limited to legged robotics, reinforcement learning, motion planning, manipulation, swarm robotics, and perception. At WPI, I also worked as a Student Assistant (Undergraduate Teaching Assistants) for 2+ years for the sophomore level robotics classes focused on mechanical design and sensing. I held weekly C++ coding workshops, homework help sessions, lecture reviews for 400+ students during my tenure. My favorite part: debugging hardware and software bugs for the final projects.

Please have a look at my CV if you want to know more about my professional journey

Research Interest

I want to democratize robotic deployment beyond the traditional cages and into more human centric spaces by researching at the intersection of generalized learning, planning, and control applied to make humanoids and mobile manipulators capable of versatile long horizon task execution.

Most of the current robotic deployment exists in the traditional Industrial and manufacturing settings. These industries typically have well-defined repeated processes at scale. So when these industries are trying to automate, they are looking for robots that can do one or maybe a couple of things really well because that’s all they are concerned with. These industries can sequentially deploy different robots that in aggregation automate the different parts of the process. Specialized robots AMRs and manipulators with specific end effectors have perfectly fit into this paradigm and are most of the robot deployments we see currently.

However, this paradigm does not really work when we are talking about consumer centric use cases of robots. In these scenarios, there is a need for robots that can do diverse things, be taught new things, and work in a lot of different environments. Specialized robots impose a lot of spatial constraints required for their deployment and operation. Since most of the space is designed for us humans to operate in, a human-like spatial compatibility is essential to be eligible for operation in diverse use cases. Furthermore, if these robots serve only a specific use case, it is very costly for consumers to buy multiple of these for different use cases with low volume throughput. We often need to do one thing at a time and another at a different time and cannot really buy robots for each use case. For general human collaborative uses, there is a need for general-purpose robotic platforms that can seamlessly operate within human spaces, do a wide variety of tasks, and have a force-multiplying effect on productivity through humans. I believe the answer lies in building general-purpose mobile manipulators like humanoids, legged robots with manipulators, and wheeled robots. For example:

- Home: Do you really want 5-6 robots inside your house or a general-purpose one that can operate in most spaces of your house and that can dust your surfaces, load/unload the dishwasher, and clean your toilets? If you are able to easily teach them specific tasks you want them to do, even better!

- Manufacturing and Warehousing: Specialized robots do a lot of the processes in these industries. However, you still see humans running around doing a lot of ad hoc and repetitive work. Generalized human-like robots would be a great assistant to pass work from one specialized robot to another without moving entire assembly lines or imposing other spatial constraints.

- Exoplanet Bases: This is truly a long-term vision but bear with me! If the idea is to create an exoplanet civilization through bases on the Moon and Mars, there will be a need for helping hands that can operate in dangerous, diverse, unstructured terrain of these planets while also operate inside the human form compatible structures. Given the limited number of humans that can be sustained initially, robots are a great force multiplier. I cannot think of anything better than a general-purpose mobile manipulator like a humanoid or a legged robot with a manipulator for this use case.

Projects

Multi-modal Locomotion Robot

Abstract: A variety of animals such as primates, dogs, and bears switch modes of locomotion between quadrupedalism and bipedalism to better complete certain tasks. However, very few robotic platforms can effectively combine the two forms of locomotion. A multi-modal robotic platform with such capabilities would provide additional adaptability in unstructured environments, broadening its potential applications. Therefore, we extended an existing quadrupedal platform with the capability to transition into a bipedal stance. In this project, we built a physical robot, developed an accompanying software stack with a reinforcement learning pipeline, implemented quadrupedal locomotion, and achieved stance transition in simulation. Our integrated hardware and software platform affords future roboticists the opportunity to test and develop more adaptable locomotion strategies and increase the functionality of robots more broadly

Project Page – Paper – Poster – Video

A. Euredjian, A. Gupta, R. Mahajan, D. Muzila, “Multi-Modal Locomotion Robot,” Worcester Polytechnic Institute, 2021

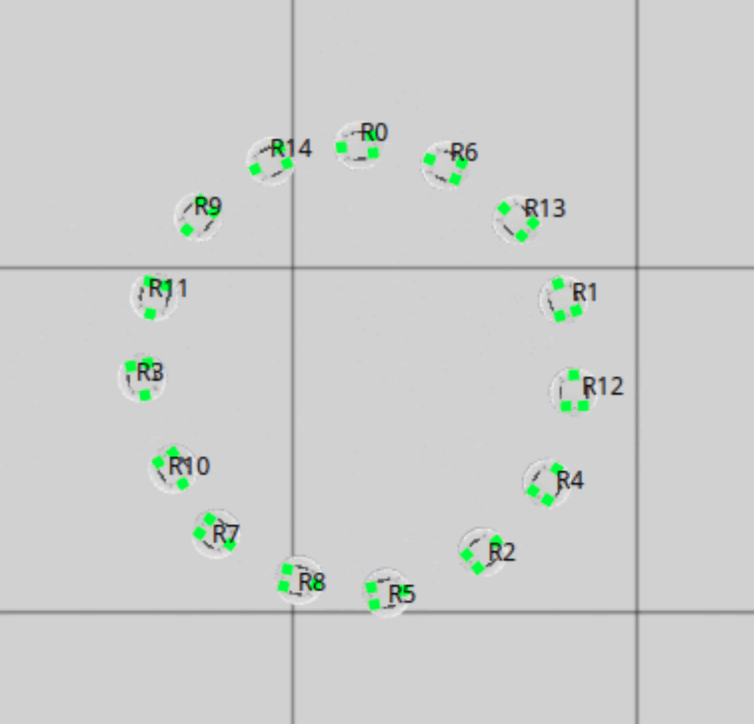

Endogenous Fault Detection

Abstract: Robots in a swarm can achieve complex objectives by splitting them into smaller tasks and achieving these sub tasks with decentralized coordination. This decentralized behavior is responsible for the inherent robustness and scalability of swarm systems. But swarm systems are not devoid of faults. Like all robot systems, they can fail. In order to realize the full robustness potential, the swarm systems need to be able to detect and isolate faults within themselves. In this paper, we implemented an endogenous fault detection strategy on a swarm of robots exhibiting a circle following behavior.

Paper

A. Euredjian, R. Mahajan, H. Saperstein, “Endogenous Fault Detection for Circle Following Behavior,” Worcester Polytechnic Institute, 2021

Multi-environment Reinforcement Learning Agent for Robotics Tasks

Abstract: Reinforcement learning (RL) has shown great promise in enabling robots to perform complex tasks, yet most approaches train models for individual environments, limiting their generalization capabilities. In this work, we address this limitation by developing and evaluating generalized RL models for multi-environment robotic tasks. Using OpenAI’s Fetch and Pick Place task as a testing environment, we developed a single actor that is able to perform both these tasks at a comparable success rate with OpenAI’s specialized models. The dual-critic approach achieved high accuracy in multi-task learning by lever- aging independent critics, while the environment-aware model provided a stable yet slightly less effective alternative using a single critic. The generalized model performed much better and showed lower variance in results when the data being trained was alternated more frequently. Our findings suggest that generalized RL agents can be trained to effectively learn and perform across related environments.

Paper – Poster

P. Argyrakis, R. Mahajan, “Multi-environment Reinforcement Learning Agent For Robotic Tasks,” Worcester Polytechnic Institute, 2020

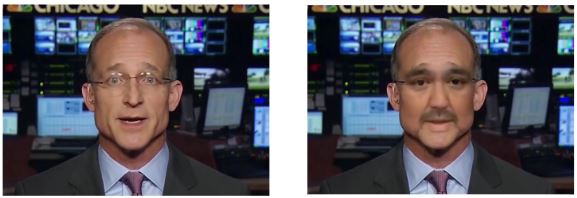

Deepfake Detection and Classification

Abstract: Recent advancement in computer vision techniques have led to a surge in deep fake videos and images flooding. Deep fake is a term coined to represent fake images generated using deep neural networks. These videos and images can have a profound impact on world politics, stock market and personal life. With this paper, our team summarizes past work in this field and then focuses on creating a network architecture to classify these deep fakes.A CNN architecture is implemented and trained and many insights into the problem of deep fake classification are discussed.

Paper

P. Jawahar, S. Koenke, R. Mahajan, “Deepfake Detection and Classification,” Worcester Polytechnic Institute, 2019

Social Implications

Should Robots be Taxed?

We are in the midst of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4th IR). This revolution is fueled by the breakthroughs in technology like artificial intelligence, robotics, and 3D printing. These technological breakthroughs are commensurate to the ones witnessed in the previous industrial revolutions. An estimated 400 to 800 million workers can be displaced by automation in the world by 2030. Of these displaced workers, 75 to 375 million will need to switch occupations and learn new skills. For the United States specifically, one-third of the workforce may need to find new occupations and skills.[1] Given these predictions, there is a genuine concern of unemployment in the near future………….

Paper

Challenges With Integration of Co-Bots in Society

In the past decade or so, robots have started to play a bigger role in the commercial and industrial sectors. According to the International Federation of Robotics (IFR), 422,000 robots were shipped globally in 2018, amounting to $16.5 billion. IFR expects this number to grow by 12% by 2022[1]. This indicates a growing demand for these robots in the industry. New concerns are being raised with this growing demand. After we went through the computer revolution and did not prognosticate its impact on society, there is more pressure to not make the same mistake with the upcoming robot revolution. So far the majority of robots in use are in an isolated industrial setting. For example, an industrial robotic arm is usually enclosed within a cage. Whenever a human has to enter the cage, it is made sure that the arm is turned off so it cannot accidentally harm humans. This is not the same case for collaborative robots or cobots. Cobots and humans usually have a major overlap in their workspaces. The major distinction between these cobots and industrial robots is that the former is designed for direct interactions with humans while the latter is not. For example, Miso the burger-flipping robot is designed to be incorporated in the kitchens of restaurants and is supposed to work in close contact with humans………….

Paper